I promised to follow up on my presentation on the Fear and Pain Epidemic this week. The takeaways were BIG - big picture, big ideas, and a big change from the way we have thought about solving the opioid epidemic in the past.

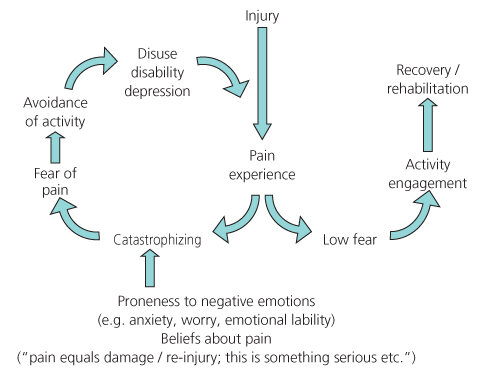

First, it’s important to understand the fear and avoidance cycle that can get triggered after a painful event and cause what we call chronic or persistent pain, which is pain that persists beyond the normal course of healing from an injury. Two people can have the same experience of pain after an injury. One who has low fear of pain, based on previous experience or conditioning or lower anxiety sensitivity, etc. will continue to engage in activity and will achieve recovery or rehabilitation. The other individual, who experiences higher fear and catastrophizes the fear experience, which is influenced by their proneness to negative emotions or anxiety sensitivity, distress, and has unhelpful beliefs about pain – that it means damage, that it might be permanent, that it will be very difficult to deal with – experiences more fear of pain, which leads them to avoid activities related to the injury and that might be helpful in rehabilitation, and so the injured part falls into disuse, they might identify more with disability (which is then self-perpetuating), and fall into depression, all of which perpetuate the experience of pain on and on, which becomes chronic.

So, using this model, it gives us a lot of points of intervention to make strides in treating fear and pain, other than targeting the opioids. Catastrophizing can be treated preemptively by setting reasonable and realistic expectations about the pain experience, if possible – letting people who are facing surgery or other rehabilitation from injury know what pain they might experience and that pain is a part of the recovery process. When we know pain and related fear may arise, we can teach people ways to engage their parasympathetic “rest and digest” system to counter overactivity in the “fight or flight” system. This includes mindfulness practices, relaxation, breathing exercises, and physical practices like yoga that focus the mind and cultivate feelings of safety within the body. We can help people deal with their fear cognitively as well, with acceptance and mindfulness practices that reinforce pain as a signal, not something to fear and avoid. We can also help them to engage in exposure and de-sensitization therapies, to give people manageable experiences with pain that can show them, over time, that they don’t need to engage in “fight or flight” quite so quickly or automatically and that they can do some of the activities that will ultimately help them to heal. We can help people who experience pain to identify less with pain as a core part of their being, and to identify in ways other than “disabled” or with their disease. And, throughout all courses of illness or injury, we can learn about and promote alternative ways of managing pain – because these do exist and are more and more accessible! We have to help clients who experience fear of pain to see longer-term practices as more valuable than quick fixes.

Overall, the way we will solve the opioid epidemic is by using psychological approaches for fear rather than medical interventions for pain. If people can feel they have more control over their circumstances – by having choice, information that they can understand, and a sense of autonomy, that they can do something about their own health – they will experience less of the fear about pain that is the most debilitating. This includes giving information about what to expect, reducing the unknown about pain as much as possible. It includes encouraging participation and social connection, both of which can provide relief in those opioid centers of the brain. And we can be the ones who pay attention to people’s moods and their personal experience of pain. Where physicians must be the ones who ask us to “rate our pain on a scale of 1-5,” we can be the ones who take time to talk with people about their fears about pain, beliefs, expectations, anxiety levels, and ways to empower them to disengage from the cycle as much as they can.

Lethem, J., Slade, P. D., Troup, J. D., & Bentley, G. (1983). Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception: I. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21(4), 401-408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(83)90009-8